13年前,我刚来北京,很快就认识了厉槟源。那时,他用锤子砸出 “一封情书”,夜晚,他骑摩托从黑桥前往城市中心穿行,脚下安装的菜刀擦出数道长长的火花。

第二年,在黑桥的一个三岔路口,厉槟源坐在摇晃的椅子上扔出很多鞭炮;抱起烟花朝一条无名的臭水沟喷射绚烂的烟火,并命名为春天。那时,黑桥乱糟糟的,生计也总是一个问题。但厉槟源更在乎表达,在乎内心的火,大于北京的雪。

几个月后,他在望京夜奔的视频,在互联网上火爆。他却在成为 “明星” 和并无改变之间生活,在时代的情绪和自由个体之间徘徊。

即便如此,“北方的现实主义” 色彩仍给了厉槟源很多激励,去做别人不做的事情,去实现那些 “非常反应” 和 “莫名需求”。 神经的想法,往往有着天然的幽默感。 “禽流感” 时,他去三里屯牵绳溜鸡;人们在这座快节奏的城市挤地铁时,他在地铁里刷牙洗脸。厉槟源总是能洞察情感中的乏味、无奈、悲剧感的倾向。

2014年,厉槟源回到故乡湖南省永州市蓝山县。他在父亲遗留的一块土地上用身体击打、耕种。《自由耕种》成为厉槟源的一个转折点,也开启了一个真正的个人时刻:在此之后,一个关于 “厉槟源” 的新的命名被激活。2020年他定居在蓝山,他的锚点也从大时代的北京,回到童年与自然的河流、瀑布、清风、夜火、星辰里,这是中国人独有的浪漫,对自然与土地的眷恋。

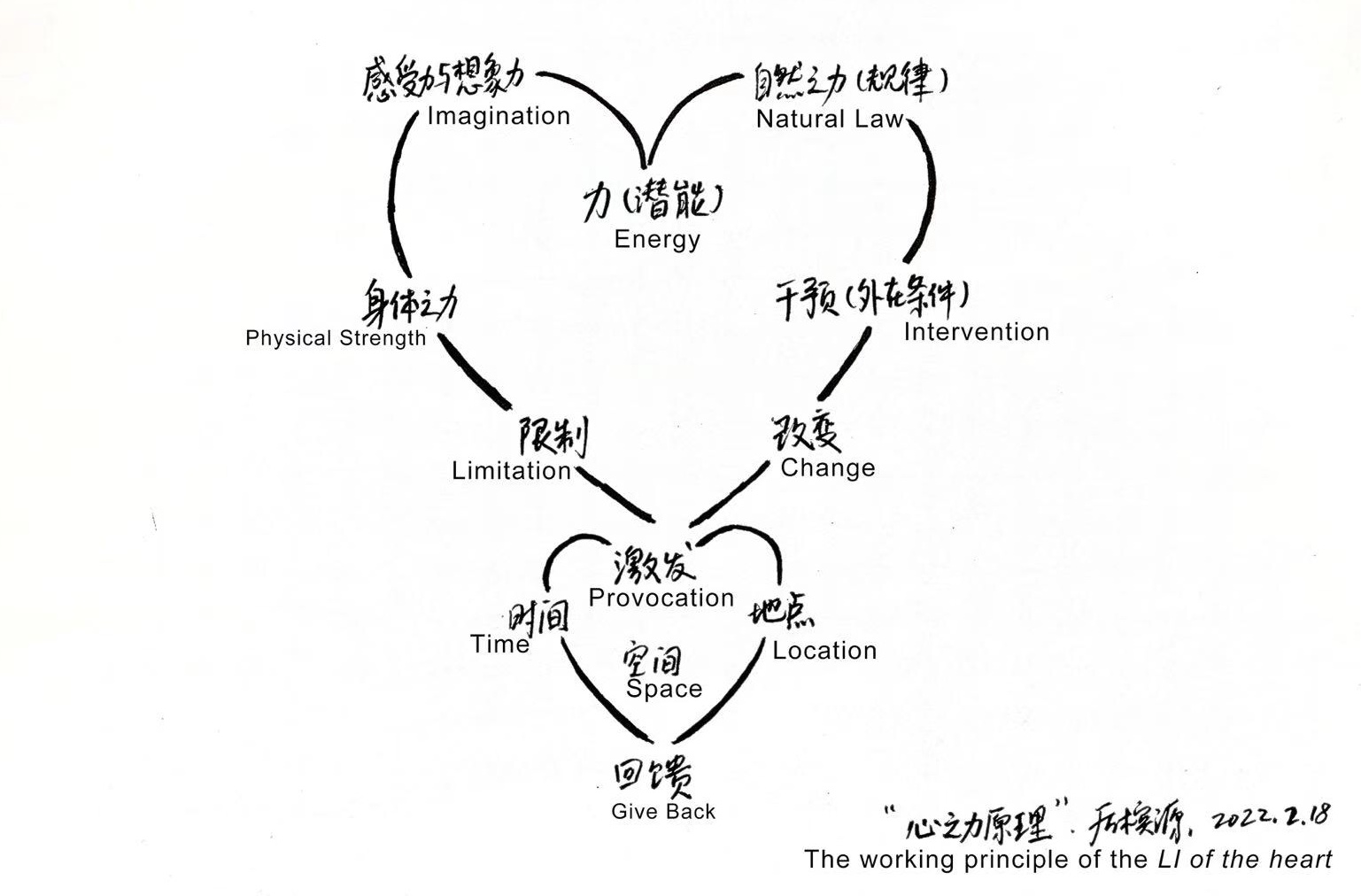

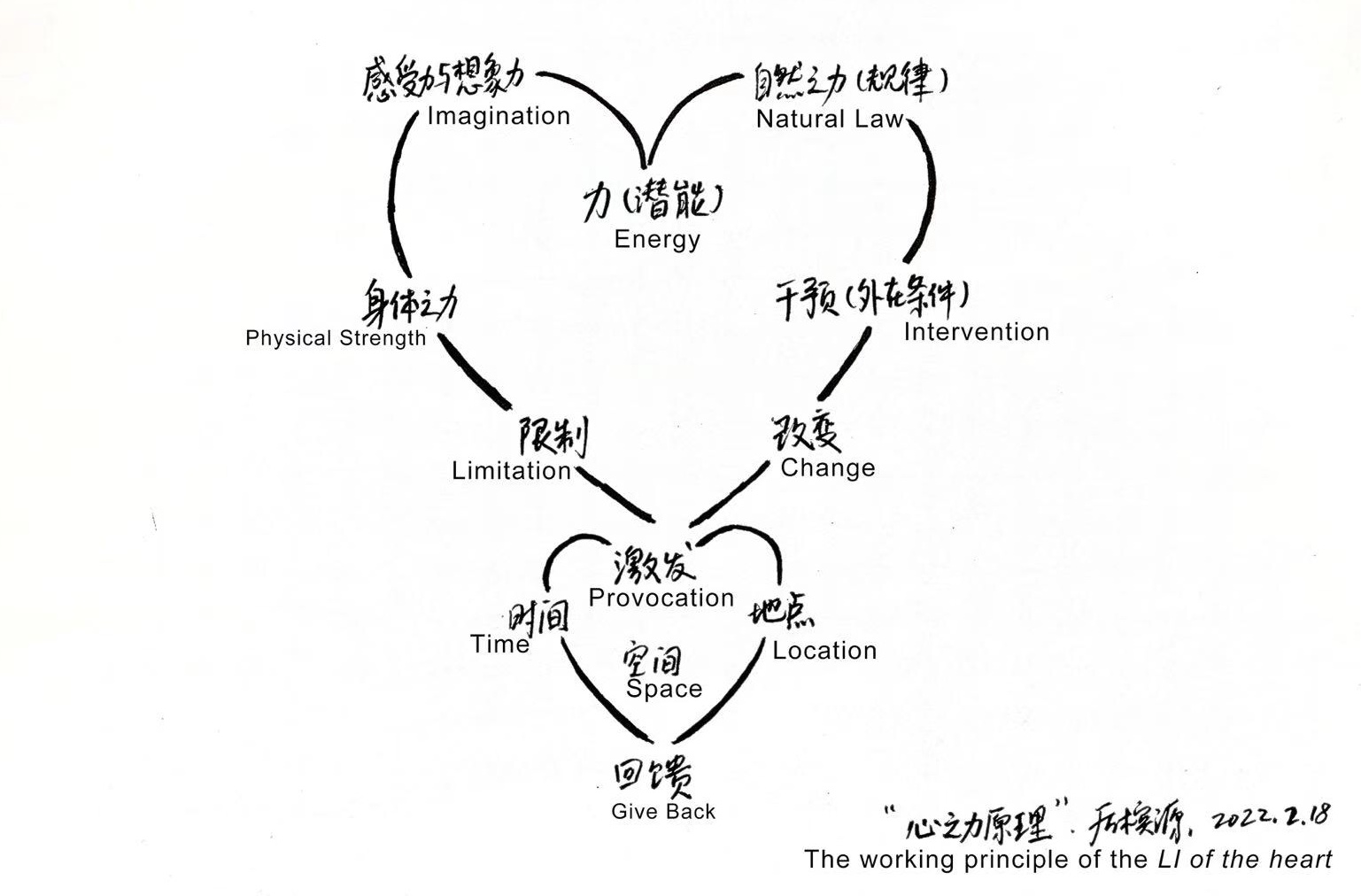

他的情感也在不久的将来,背弃他过去的形式。这种背弃,基于艺术家变化的关切,一次次地上演。某次讲座,厉槟源要讲述自己,于是他写了一个《心之力法则》:

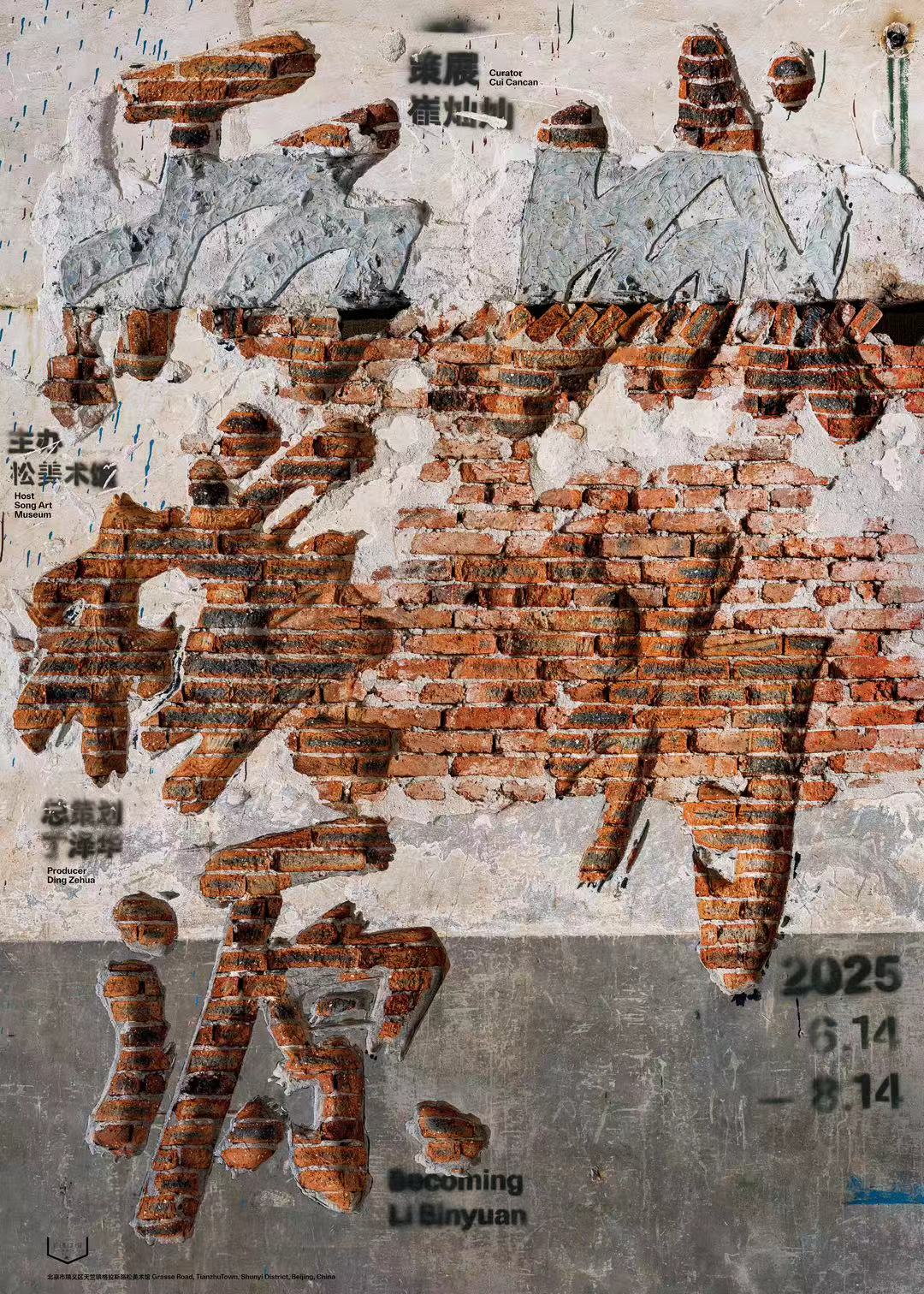

2017年,厉槟源给我看了一件名为《2cm》的作品,那是在他母亲工厂里完成的,他也第一次向我提起了母亲。三年后,他创作了那件有关父亲、令我潸然泪下的《最后一封信》。父亲与蓝山变成了一种意象,那里有着只属于他的酸甜苦辣:长眠的秘密,生命中深埋的欢喜与故乡的不解之缘。 2018年,厉槟源在韩国海边的风中扮成一只孤独的海鸟。我想起他之前许多和地点有关作品,在意大利的教堂前随着钟声站立,在一座美术馆的建设中成为工人。这是他工作方法,也造就了独特的风格。像是中国唐代的诗人一样,又像是现代城市的牧羊人,一个 “写生” 的行为艺术家。 展览的开篇,是厉槟源的两端。一端,我们将看到不同 “自画像” 的厉槟源:倒立于海面的人,在山颠迎风的人,追踪雪花的人,化作蜜蜂的人,躺在树冠的人,余晖下的人…… 这些不同状态相互作用、相互拆解,这些不同的瞬间,短暂的像是那时那刻的花火。另一端,是他跨度最长的作品,14年跨越无数空间,仿佛一条奔腾的河流携带各种经历的热情与困惑,蜿蜒与杂质,直到桥梁的倒塌,成为生命中的长情。 在厉槟源那些如英雄般的形象,或是无聊与空虚的举动里,谁说神话不是空洞?谁说空虚里不包括深刻?谁说李白诗句里 “轻舟已过万重山”,轻舟和万重山之间不是力量悬殊的浪漫? 使我们成为艺术家的,并非是艺术品,而是人的可能性的某一部分。像是泥土只是雕塑的一种材料而已,艺术也从来不是人的本质。 10天前,讨论展览方案时,我担心60多件作品太多,话题过去1小时后,厉槟源突然说了句:“一件都不能少”。之后,我突发奇想:“展厅里我就不写学术巴巴的单元文字了,就用你写的,那才是你”。是的,我们十几年的战友,受惠于现实与肉身赏赐的激情,小城青年的野生让我们有了与生俱来的 “饥饿感”,接受过知识但从没被规范,见过很多英雄与偶像,但不愿成为任何一个版本……. 这一天,厉槟源正好40岁。 成为厉槟源,便是成为自己,它需要一个特殊的人用不凡的生命去证明。像是毕加索那句名言,我本来想成为一个艺术家,却成为了 “毕加索”。同样,当成为厉槟源时,艺术史和过往的经验都不再重要了,它的核心是创造一种关乎人的期许,关乎行为的哲学,“自己” 可以成为何种形态的深刻信念。 于是,他只是不断的创造自我:成为一个诗人,保持敏感和诗兴;成为一块石头,任凭冲击与风化,生命本是耗损的过程;成为一个社会观察者,以让自己变得尖锐;成为一个游牧者,在与世界的摩擦中,忘掉经验与规律,让身心在每一个码头灵动;成为一个猎手,观察着人物、地点、故事的一举一动;成为在都市夜晚奔跑的人,在那些不确定的欲望和躁动中,成为由冲动和欲望构成的火花;成为一个行为艺术家,过不一样的生活,以抵抗平庸和乏味。 成为 “过程”,成为 “不定”,确定和不确定的事情一样多,而答案就在 “我不想成为” 和 “我想要相信” 的故事里……… 策展人:崔灿灿 I first met Li Binyuan thirteen years ago, soon after I arrived in Beijing. Around that time, he used a hammer to pound out “A Love Letter.” One night, he rode a motorcycle from Heiqiao Village towards the city center, two chef’s knives attached to his feet scraping out long lines of sparks in the road. A year later, he sat on a rocking chair at a three-way intersection in Heiqiao, tossing out firecrackers and aiming fireworks to shoot a fountain of brilliant sparks at a nameless ditch, calling it a “Spring.” Heiqiao was chaotic in those days, and making a living was always a challenge. But Li Binyuan was more concerned with expression, with the fire in his heart, which was greater than the snow in Beijing. A few months later, videos of him running naked through the Wangjing neighborhood went viral on the internet. He was walking a fine line between becoming a “celebrity” and living life unchanged, between the zeitgeist and free individuality. Even so, the “realism of the north” gave Li Binyuan a lot of encouragement to do things other people weren’t doing, to bring about those “abnormal reactions” and “indescribable urges.” Neurotic ideas often have a natural sense of humor to them. During a bird flu outbreak, he walked a chicken on a leash through the Sanlitun shopping district. As people crowded the subways in this fast-paced city, he was there in the train car washing his face and brushing his teeth. Li Binyuan is always able to sniff out the hints of ennui, helplessness, and tragedy lurking in emotions. In 2014, Li Binyuan returned to his hometown of Lanshan County in Yongzhou, Hunan Province. There, he used his body to fight and sow seeds in a plot of land he inherited from his father. Freedom Farming marked a turning point for Li, and launched a truly individual moment: after this point, a new act of naming “Li Binyuan” was set in motion. He settled in Lanshan in 2020, shifting his focus from Beijing, with its sweeping moment in history, to the rivers, waterfalls, gentle breezes, firelight and starry skies of his childhood and nature. This is a uniquely Chinese romanticism, this love for nature and the land. Not long after, his emotions would abandon his past image. This abandonment would play out over and over again, as the focus of the artist’s concerns continually shifted. Once, at a lecture, Li Binyuan wanted to describe himself, so he jotted down the diagram “The working principle of the Li of the heart”: In 2017, Li Binyuan showed me an artwork, titled 2cm, which he had made in his mother’s factory. This was the first time he had mentioned his mother to me. Three years later, he created a heart wrenching work about his father, The Last Letter. His father and Lanshan had become a form of imagery encompassing a range of emotions all his own: long slumbering secrets, a deeply buried joy of life, and an undying love for home. In 2018, along the seashore in Korea, Li Binyuan roleplayed as a solitary seabird. My thoughts were drawn to many works he had made relating to place before, standing to the tolls of the bells in front of a church in Italy, or becoming a worker at a museum construction site. This is his working method, and it has shaped his unique style. He is like a Tang dynasty poet, a herdsman in the modern city, a “plein air” performance artist. The exhibition opens at two ends of Li Binyuan. On one end, we see Li Binyuan in different “self-portraits”: a man standing on his head on the sea’s surface, a man facing the wind on a mountaintop, a man chasing snowflakes, a man becoming a bee, a man laying down on the crown of a tree, a man in the lingering light of dusk… These different states play off of each other, dismantle each other in moments as fleeting as sparks. On the other end is his longest-spanning artwork, 14 years crossing countless spaces, like a river carrying the passion and confusion of so many experiences, meandering and complex, until the bridge collapses, becoming one of the great loves of his life. In Li Binyuan’s heroic images, or in those seemingly mundane and nihilistic acts, who says myths aren’t empty? Who says emptiness does not encompass the profound? Who says Li Bai’s poetic verse, “my light boat has passed through the weight of ten thousand mountains,” is not about the romance of power disparities? What makes us artists is not the artwork but a certain aspect of human potential. What looks like mud is actually just a sculptural material. Art has never been the essence of humanity. Ten days ago, when discussing the exhibition plan, I was worried that 60 artworks was too much. After discussing it for more than an hour, Li Binyuan suddenly said, “not one less.” I suddenly had an idea: “I won’t write a bunch of academic introductory text for each exhibition section. We will use your own words, making it yours.” That’s right: we are comrades-in-arms going back decades, blessed with passion bestowed on us by reality and the flesh. The wildness of small-town youth has given us an inherent “hunger.” We have been educated, but never tamed. We have seen many heroes and idols, but we refuse to become a version of any of them…. On that day, Li Binyuan turned 40. To become Li Binyuan is to become himself, a unique person affirmed by an extraordinary life. It is like the famous words of Picasso: I wanted to become an artist, so I became “Picasso.” Likewise, when he becomes Li Binyuan, art history and past experience no longer matter. His core is the creation of hopes for humanity, and a philosophy of action. The “self” could become a form of profound faith. Thus, he is simply constantly creating himself: becoming a poet, maintaining keen poetic inspiration; becoming a stone, enduring onslaughts of wind and water, life itself a process of being worn down; becoming a social observer, in order to make himself more incisive; becoming a nomad, forgetting experience and conventions in the friction of the world, body and soul in motion at every port; becoming a hunter, observing every movement of people, places, and stories; becoming a night frolicker, turning into sparks of impulse and yearning amidst those uncertain desires and drives; becoming a performance artist, living a different kind of life in resistance against the ordinary and the mundane. Becoming “process,” becoming “indeterminacy,” where certain and uncertain things are equal in number, and the answers are in the stories of “I don’t want to become” and “I want to believe”… Curator: Cui Cancan